Sienna Bentley

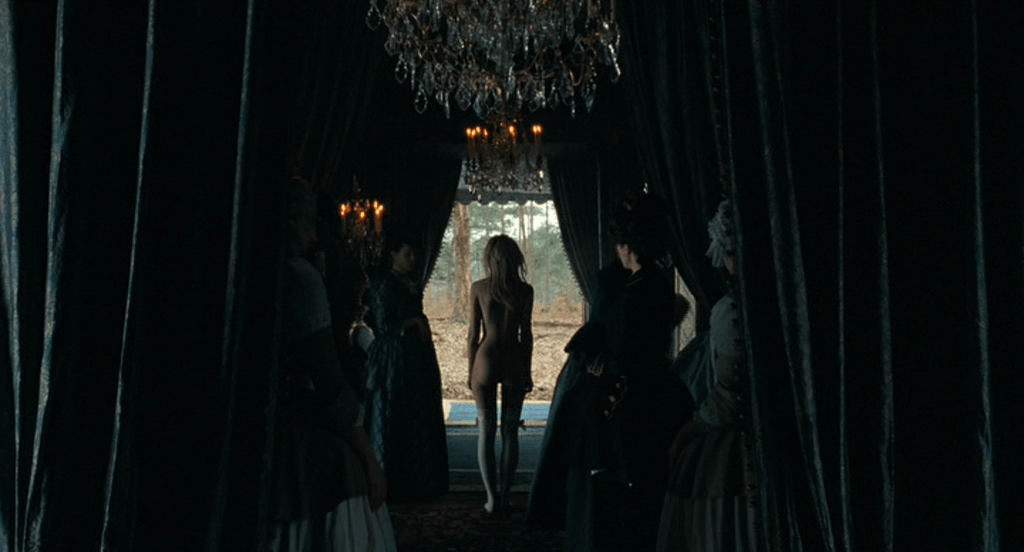

If you grew up in England and studied French and/or music around the age of twelve, you have probably watched Les Choristes (The Chorus, directed by Christophe Barratier; 2007). We were shown the French film in both classes, and it very quickly became one of my all-time favourites.

This was probably the first film where I was truly made to appreciate the importance of the soundtrack. Your attention is forced to focus on the music, as the plot surrounds a former composer, Clément Mathieu (Gérard Jugnot), whose love for music is reignited when he becomes a teacher for troubled boys. The soundtrack is therefore effortlessly incorporated into the story, and is impossible to overlook.

I was enraptured by the music itself. ‘Caresse sur l’océan’ and ‘Voir sur ton chemin’ give me goosebumps every time I hear them, and I truly believe that it was these two tracks that birthed my deep and undying love for minor chords.

However, as I got older, I began to understand why the film was so hard hitting (aside from its ending, which makes me bawl every single time). It exemplifies perfectly the far-reaching and poignant impact of music, and its ability to change lives. It also explores profound ideas about what it means to be a failure, which is something I have grappled with myself for years.

Music changes lives

Les Choristes takes place in 1950 at a school for troubled boys. Our first introduction to their behaviour is when the caretaker (Jean-Paul Bonnaire) is the victim of a prank in his office, which nearly blinds him. Clément Mathieu is unable to control his class, kids are often locked in solitary or flogged for bad behaviour.

As soon as Mathieu realises that the boys can even sing, he is inspired to dig out his old sheets. What’s interesting is that they don’t seem to even just humour him – they don’t question him at all when he makes them audition and they don’t laugh or joke when they do. He captures their attention simply just by getting them to bang their hands on the table to keep a rhythm.

The music represents hope. As the choir practises and improves, life at the school seems to change for the better. The bitter, abusive headmaster, Rachin (François Berléand) – who is completely against the idea of a choir from the outset – seems to soften as they all play football together, the children stop getting into as much trouble. In a way that is comparable to The Sound of Music, music brings light into the previously strictly regimented lives of the children and teaches them how to be just that – children.

The impact of music is more obviously displayed through the character of Pierre Morhange (Jean-Baptiste Maunier). He is the most resistant to the choir – and the most gifted. Mathieu goes to great efforts to nurture Morhange’s talent, even helping him get a scholarship to a music school in Lyon. Music offered him a way out of a dire situation that didn’t seem to have a light at the end of the tunnel; it gave him something to work towards, a passion. It’s in his eyes, too; while they are often cold and hard, when he sings, they are full of hope and gratitude. And we know that his life is forever changed as the film opens with him as an older, highly accomplished man (Jacques Perrin) in the classical music industry, accredited on magazine covers as being the world’s greatest composer.

An underground resistance

When the headmaster forces Mathieu to disband the choir, they are forced to practise in secret. It is literally described as an “underground resistance”. There’s an interesting irony there; the rebellious troublemakers, who have a history of doing bad things and hurting themselves and each other, are being made to hide something that is actually good for the soul and is actively changing their behaviour. They continue to learn the music and lyrics outside of rehearsal, showcasing their appetite for music and thirst to be better.

There’s a wider ‘worker-bee mentality’ conversation to be had here on Rachin’s reasoning. The headmaster is portrayed as being very profit-driven; he takes credit for the choir when the benefactors visit and asks the Countess (Carole Weiss) about his rosette and money. It is very possible that he was aware that introducing music into the children’s lives would make them harder to control. When they behaved badly, there was a strict retaliation policy (”action, reaction”), whereas, even though they were proven to be better behaved, music made them somewhat unpredictable and taught them to think for themselves. As a school built to house and discipline ‘lost causes’, what happens when they are no longer lost?

I think this just proves how educational music is, and thus how crucial it is as part of a curriculum. We see the children learn – they learn how to sing, read music and work as part of a team. They also become more creative and imaginative, as they work together to invent a new playground game.

What is the definition of ‘failure’?

Towards the end of the film, when Mathieu is walking out of the school’s gates, he reminisces about being a failure. He says, ”I’m Clément Mathieu, a failed musician – no one even knows I’m alive”. He thinks, as many do, that because he did not achieve notoriety for his passion, he is a failure. But does fame equal success?

Ultimately, the film focuses on the fact that music is able to – and does – change lives. Not only was Morhange’s path altered from being one of the biggest troublemakers to having a bright and promising future, but the introduction of Mathieu, and therefore music, to the school changed all of those boys’ lives. He had such a deep impact on them as a teacher and they performed his music to many people, even when he wasn’t there to conduct them. It taught them how to find joy and hope for something better.

Although no one knew Mathieu’s name, these kids reignited his passion for music. Prior to taking the teaching position at Fond l’Étang, he’d vowed to never compose again. They inspired him to do so. And he didn’t stop – he taught music lessons for the rest of his life. He pursued his passion and was able to indulge it for many years – that doesn’t sound like failure to me.

This idea of being a failure if you don’t receive notoriety is something I think about often. As a musician myself, if I don’t make music my full-time career and achieve fame and ‘success’ (whatever that is), does that mean I failed at music?

Personally, I don’t think ‘failure’ actually even exists, but even less so when it comes to creative outlets like music. If you make music, you are a musician – not a failed one.

At its essence, the film – and I – encourage you to pursue your passions. You never know the effects it could have on others, and the key to a happy life is doing exactly what brings you joy, whether you deem yourself to be good enough at it or not.